Real Freedom

Deep within the American mind is the false belief that we can only be more equal by being less free.

Post 4: 28 January 2025

Deep within the American mind is the false belief that we can only be more equal by being less free. We are confused about the sort of equality we need. And we are fundamentally wrong about what freedom is. These mistakes narrow the range of the politically possible in the United States. They are major reasons why we are not as free, and not as equal, as we ought to be, or could be. We have to do what we can to fix this. I have already written a bit about the kind of equality that full membership requires; now I want to focus on freedom. This week, I’ll describe two ways philosophers have characterized freedom. Next week, I’ll talk about how this connects to my own views and to the project of social citizenship.

The fundamental problem is this: Most of us fail to recognize that unequal opportunity, inadequate education, and economic insecurity in all its forms make us less free. These inequalities are unsettling, but can we let them clash with our useful belief that we are equal persons who hold equal rights and therefore have equal liberty? Within this divide are two incommensurate understandings of what freedom is all about. You can try to paper over this chasm—John Rawls rescues the semantics by referring to “the lesser worth” of “equal liberty”—but freedom has more work to do than this.1 It is more than a generic attribute of the human personality; it is, as John Dewey wrote, “something to be achieved.”2 And achieving freedom is, or ought to be, the mainspring of all political action.

In America, our dominant public philosophy—“traditional” liberalism—defines freedom as the absence of coercion.3 This is how we usually talk about it: we are free when governments do not interfere with our legitimate private choices. In the domain of personal conscience, this works well enough. Governments ought to be neutral; they should not tell me what makes a good life, what to think or believe, or how to worship. In this way, the state protects our freedom, mostly understood as a natural human trait.

But when we face the problem of economic inequality, the approach breaks down. Constructed as a means of resisting the power of the state, traditional liberalism provides governments with no tools with which to check concentrations of private power or to lift up the working class. This is partly so because liberalism is suspicious of any use of state power—certainly the correct posture, as the state is dangerous—but also no framework for working through that suspicion (modern egalitarian liberals provide some options). Worse still, liberal ideas were originally crafted in part to defend the emerging bourgeois conception of private property. This actually provided an individualistic moral justification for extreme wealth inequality.4 Most important for social rights, it provided reasons for governments not to interfere on behalf of the poor. Not only was liberalism not constructed to fight material inequality, one can argue that it causes it.

The principle of neutrality, applied uncritically, requires treating the most powerful private economic actors and the poorest workers as equals, and treating any state interventions intended to level the obviously uneven playing field as injuries to the basic economic liberty to enter into contracts, an assault on the freedom of both the great and the small. This laissez faire logic has both legal and political power. In court, it underpins the judicial dogma that blocked most economic regulations and unionization efforts and limited the scope and effectiveness of the Fourteenth Amendment during the entire period between Reconstruction and the New Deal.5 We are not rid of this legacy; indeed, it has made a strong comeback in today’s Court. I’ll have a lot more to say about this in later posts.

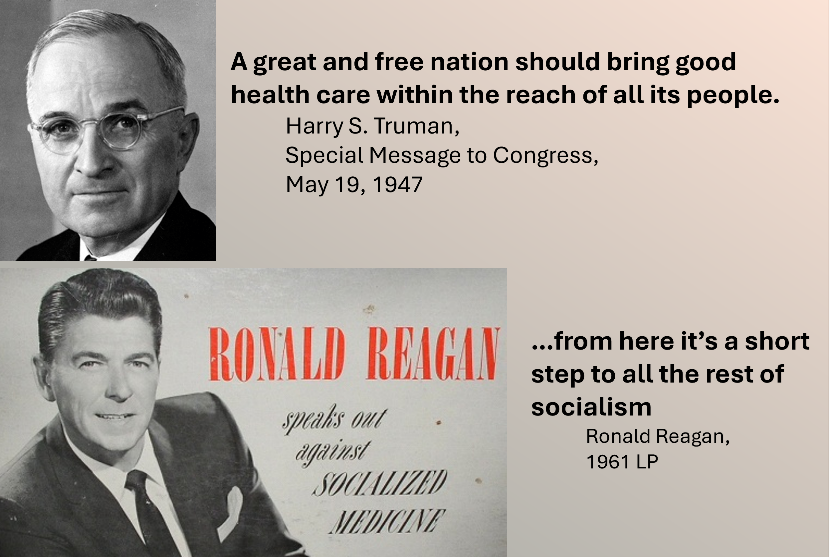

In popular politics, this line of reasoning has formed the core of the ideological opposition to egalitarian social policies since the New Deal. Any effort to leverage the power of government to ensure that Americans have access to basic goods is characterized as a threat to freedom. This strategy has been very effective in slowing progress. Consider, for example, the halting and still incomplete 75-plus year effort to enact universal health insurance. The standard attack on these proposals is that any public role in ensuring access to care is “socialized medicine”—a cascade of restrictions on personal choice that ultimately threatens basic freedoms. This is the claim wielded successfully against Truman’s failed proposals in the 1940s and Clinton’s failed one in the 1990s. In between, Ronald Reagan famously tried this argument against Medicare in the 1960s but fortunately failed. It is worth listening to his speech about this, issued as an LP in 1961 (see end notes). In eleven or so minutes, he mentions threats to freedom at least seven times and emphasizes the “compulsory” nature of these programs at least three times. The drafters of the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare or ACA) avoided compulsory elements, which dramatically weakened the legislation, but were still attacked roundly on the same terms. The law was characterized as a grotesque overreach of state authority (remember the dreaded “death panels”?) and even the very weak penalties for non-coverage were ultimately dropped a few years later. The ACA passed, barely, and has survived efforts at repeal, barely, but its enactment arguably cost Democrats their Congressional majority.

Even though the “freedom” argument is still very effective, it is obviously wrong. We all know someone who could not leave their job for fear of losing health insurance coverage. They are clearly less free because of this constraint. Conversely, the ACA, by reducing this personal restriction, has given people more choices; it has made them more free. From a traditional liberal perspective, this is a paradox: how could governmental “interference” in the “free” market for health insurance make us more free? Rhetorically, the standard response is to invoke a “slippery slope” or “camel’s nose” argument—a small innocuous step toward tyranny. Reagan used this trope as well in 1961: these proposals seem benign, he implored, but look where they lead.

But there is no paradox. The ACA really did make people more free. To see this, we need to reach back to how people thought about freedom before the liberal notion of noninterference became so dominant. Because these ideas can be traced back to ancient city republics, we’ll label them civic republican.6 In this older view, individual freedom depends on the ability to make undominated choices, a degree of economic, social, and political independence from the undue influence of others. The critical difference is this: Your personal freedom is compromised whenever others are in a position to exert coercive control over you, whether they are actively coercing you or not. For the ancient republican thinkers, this was self-evident: the slave of an absentee master may never be directly coerced but is still not free. We live less extreme examples than that but surely understand that the better part of power is exercised through relations of domination rather than direct coercion and threat, which are costly. How much does success in chess depend on “controlling” the board rather than on attacking the opponent directly? Large corporate campaign donations are not dangerous because the funders will demand quid pro quos; politicians dependent on these funds will anticipate these demands and comply in advance.7

The most critical implication of this classical view of freedom is that anyone who depends on others for basic needs is not properly free. For classical republicans, that included anyone who was employed by someone else. How could they make independent decisions when their livelihood depended on their boss? This logic is exclusionary. Because of it, most versions of republicanism have been aristocratic: only the most advantaged can pass this test of personal independence to be free and therefore be considered full members of the community. This is dark, but that doesn’t make the basic insight incorrect. Real freedom requires a degree of personal independence. To be free, Philip Pettit wrote, is to “think of yourself as someone able to choose.”8 If someone else holds a dominating position over you, how can your choice reflect your own preferences?

Fortunately, the solution to this problem need not be aristocratic. Thomas Jefferson distrusted manufacturing development (and cities in general) based on exactly this sort of logic. His solution involved a fair bit of deferential politics, to be sure, but he also sought to build and maintain America as a republic of yeoman farmers—men who would be mostly self-sufficient and therefore with the independence of mind necessary for self-governance.

Today, we have a different, and better, solution. Since being free requires being in a certain socioeconomic position, it is our collective responsibility to ensure that every citizen can achieve this position.9 This insight provides the philosophical grounding for the social rights of citizenship. It also provides a framework for justifying the needed governmental action: state interventions that make people more free are legitimate. Importantly, we are talking about private inequality here—the area where liberalism is almost entirely silent. As Philip Pettit writes, “The republican theory of social justice…requires that people should enjoy freedom as non-domination in their relationships with one another.”10

More on Civic Republicanism. I will write often about the advantages of the civic republican approach (to freedom and to politics in general) as a complement to liberalism—these need not be in conflict. For anyone interested in exploring, here are two resources: First, I rely very heavily on the work of Philip Pettit, especially his 2012 book, On the People’s Terms (Cambridge), for a modern understanding of civic republicanism. Second, Quentin Skinner provides a great guide to the differences between liberal and republican ideas of freedom. See his 1998 book, Liberty before Liberalism (Cambridge) or his extraordinary 2016 Stanford lecture called “A Genealogy of Liberty” available on YouTube. [

].

Next post: Freedom and Social Citizenship (4 February 2025)

<All of the posts in On Social Citizenship connect. I recommend that readers go back and read the first entry in the series.>

—

Notes

Read what Harry Truman said about health care at The Truman Library. https://www.trumanlibraryinstitute.org/health-care/.

A YouTube audio file of Reagan’s remarks is available at the Reagan Library. “Ronald Reagan speaks out on Socialized Medicine” (Audio file), Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation & Institute.

1. John Rawls, A Theory of Justice, Revised Edition (Harvard, 1999), §32.

2. John Dewey, Liberalism and Social Action (Capricorn Books, 1963 [1935]), 26.

3. “Traditional” liberalism refers to the philosophy as it developed from John Locke through the 19th century peaking, I would say, with the work of John Stuart Mill. This tradition is most evident in thought we now label “libertarian” or “neoliberal”, in the 19th century from writers like Herbert Spencer (e.g., The Man versus the State) or William Graham Sumner (e.g., What Social Classes Owe to Each Other) and in the 20th century, Milton Friedman and his followers (see, Capitalism and Freedom) or, if you are more academically inclined, Robert Nozick (Anarchy, State, and Utopia). One of my themes is that this tradition is a much more powerful part of our collective psyche today than we generally acknowledge.

4. John Locke, Second Treatise of Government, in Locke, Two Treatises of Government (Mentor, 1960). See, especially, Chapter 5 “On Property.” In §50, he writes that “Men have agreed to disproportionate and unequal possession of the Earth.” There is a paradox here that I will explore in later posts: the formal assertion of individual equality became one of the foundations for the actual material inequality we experience in the world.

5. On this, see Joseph Fishkin and William Forbath, The Anti-Oligarchy Constitution (Harvard University Press, 2022), especially 141-150. This is a wonderful book. Traditional liberalism is more embedded in the Court than in any other American institution.

6. I take this label from Philip Pettit, but I have also seen “neo-Roman” and “civic humanism” used to cover this same philosophical territory. I almost want to apologize in advance for confusions between little-r republicanism and the name of the party, or for the fact that much of “conservatism” is “liberal”—I mean, how confusing can we make this? But I want to use labels like these in precise a way as I can to group families of ideas. The fact that they get hijacked by politicians for rhetorical reasons (they have *always* done this) is not really my problem, though it is a good topic for discussion.

7. The Court, applying a strictly liberal standard, has found that corruption requires a traceable quid pro quo. Indeed, in a 2023-2024 case, they found that making the cause and effect case requires that the official corrupt act follows the bribe, otherwise the payment could simply be interpreted as a “tip.” (Snyder v. United States) https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/23pdf/23-108_8n5a.pdf . Though a bit off-topic for this publication, this case illustrates well the difference between the liberal and republican mindsets. For traditional liberals, a corrupt act must have a clear and direct transactional element. Civic republicans, on the other hand, see corruption as inherently relational: one “own” a politician, who will then serve their benefactor without further instruction.

8. Philip Pettit, On the People’s Terms (Cambridge, 2012), 32.

9. See Desmond King and Jeremy Waldron, “Citizenship, Social Citizenship and the Defence of Welfare Provision”, British Journal of Political Science 18 (1988):415-443.

10. Pettit, People’s Terms, 77.