Post 9: 4 March 2025

In my previous posts I argued that “civic republicanism” provides the philosophical grounding for the project of social citizenship. In particular, the civic republican conception of freedom explains why we have a duty to guarantee that each person have access to an adequate level of certain basic goods—including education, healthcare, housing, and income. My reading of American history is that our biggest advances in social rights, real and promised, rested on republican principles, though this lineage was not usually acknowledged. And it will be my claim that future advances similarly must rest on republicanism.

The biggest problem with this argument is that Americans don’t know what civic republicanism is. For most, Republican is the name of a party, associated with “conservatism” in some vague way. Sigh. I am resigned to this and other name game confusions. Two weeks ago, I explained that the labels we use for political binaries and the proper names of the underlying philosophies are connected in complicated and sometimes contradictory ways (Three Political Languages & Part 2). We need to be grown-up enough to navigate this and eschew the easy openings for sophistry it creates.

This still leaves me with my more basic problem of explaining why the way forward can and must rely on civic republican principles. I start down this path today by giving some more background about civic republicanism, often by contrasting it with liberalism. You will see that the ideas of republicanism are familiar, even if the label is not. This will take several posts. Today, I want to start with the idea of citizenship.

Republicanism focuses on the office of citizen. Immigration questions aside, in our liberal society, we often use the term citizen as a synonym for person. This reflects liberalism’s emphasis on individuals as private actors and its general inattention to our public-facing roles. By asserting universal membership—correctly—liberalism effectively has no theory of membership, of what it means to be a member. In republican thought, citizenship is an office, the person’s public position in the community attached to a specific set of rights and duties. Besides jury duty, most of the traditional citizen duties have faded, especially those related to military service, the central obligation in many iterations of republican theory.

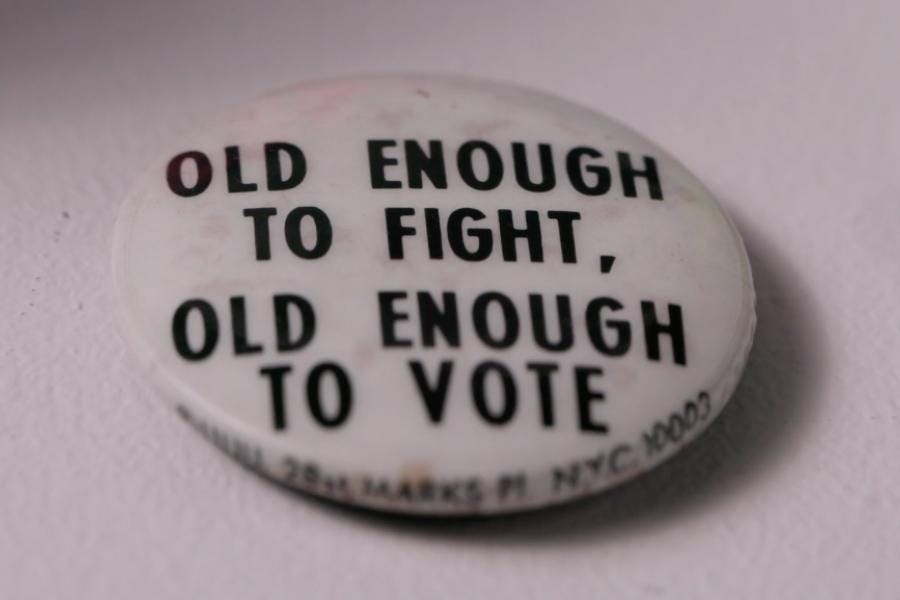

The cultural imprint of these duties remains, however. It is evident in the strong support for the military, generally seen as the institution having the most positive impact on America.1 I think that this reflects both a bit of collective guilt that the rest of us do not do enough and an endorsement of the civic virtue demonstrated through service. Part of our sense of self worth comes from our understanding of ourselves as contributing to, and having a stake in, the community. Liberal rights attach to persons, supposedly without conditions, but there is still a lingering republican sensibility that skin in the game matters. Aristotle said that “those who possess arms are the citizens” and there has always been a basic truth to this.2 The drive to expand the suffrage to 18-year-olds, which dates back to World War Two, was grounded in the slogan, “Old enough to fight, old enough to vote.” Even more telling is the continued strong public support for public service. In a 2017 Gallup poll, 49% of Americans endorsed one year of mandatory service.3 It is hard to conceive of a less liberal idea.4

Our understanding of “civic virtue”, roughly understood as public spiritedness, has deep civic republican roots. Civic virtues are promoted as the main cultural bulwark against the inevitable decay of republics. Our liberal principles tell us that individuals are free to choose their own desired level of involvement in public affairs, including whether to vote, but we recognize the virtue of engagement when we observe it in others and understand it as a measure of the overall health of our community. Republican virtue has both external and internal foci and this emphasis shifts depending on the current perception of threat to the republic. If the threat is external, virtue emphasizes the need for every citizen to contribute to the defense of the community, especially through participation in the militia. This is echoed in the term itself—virtue (virtus) means “manliness” in Latin. The core internal threat is that the pursuit of private interests will obscure the public good, either by detracting from public engagement or, worse, mobilizing the power of the state to serve narrow interests. This is manifest in the concern for controlling what Madison called the “mischiefs of faction” in Federalist 10.

There are “liberal virtues” too, which we also embrace, but these are individualistic and tend to be bourgeois values—such as temperance, reliance on reason (rather than “passion”), and delayed gratification—that have capitalist payoffs. Where our liberal selves see ambition, drive, and clever initiative , our republican souls tend to see selfishness, dishonesty, and self-dealing. For ordinary people, the private virtues of liberalism rarely conflict with the public virtues of republicanism; we can pursue our own interests and still advocate for the public good. But the two value systems conflict when powerful private actors try to mobilize or capture the state to advance particular interests. The concentration of wealth has made this a standing threat to the American republic, with the oligarchs currently having the upper hand.5

These two worldviews can be reconciled. Tocqueville squares the circle by arguing that self-interest must be “properly understood.”6 The exercise of virtue is not “self-sacrifice” but a sacrifice of small, short-term interests in favor of larger, longer-term ones. We all remember Warren Buffett comparing his and his secretary’s tax rates.7 Buffett could merely have been expressing a republican sentiment—a concern for the public good—but he also understood that a fairer tax system serves his long-term interest in economic and institutional stability. More prosaically, homeowners without children in the public schools can support school spending, not just because that is what’s best for the community, but because it increases the value of their homes. Sometimes, what’s good for the country is good for GM.8

Citizenship is a sphere of equality. Whatever other manifestations of inequality may exist, people are exactly equal across the set of rights and duties defined by citizenship. The equality of full membership is strict. It requires that persons not only have equal rights, which liberal principles ensure, but that they are equally capable of exercising these rights. According to Philip Pettit, we will know if we achieve this degree of equality when every person can pass what he calls the “eyeball test”: “They can look others in the eye without reason for the fear or deference that a power of interference might inspire.” Passing the eyeball test implies that each person attain “a certain threshold of resourcing and protection” so that they have access to a “range of choices” comparable to others in society.9 In my entry titled Real Freedom, I noted that insisting on this degree of equality has a dark side. One way to meet the high standard for membership is to restrict it to only those with access to the necessary resources. This exclusivity still gives republicanism a bad name. But this hierarchical option is not available in a liberal society that begins with the assumption that all persons are equal—citizenship is universal. The only way to satisfy both our liberal and republican principles is to guarantee everyone access to the required resources. The social rights of citizenship are those guarantees.

Next post: The Lost Roadmap (11 March 2025)

<All of the posts in On Social Citizenship connect. I recommend that readers go back and read the first entry in the series.>

Notes

1. See, for example, Amina Dunn and Andy Cerda, “Anti-corporate sentiment in U.S. is now widespread in both parties”, Pew Research Center, 11/17/2022. Online at https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2022/11/17/anti-corporate-sentiment-in-u-s-is-now-widespread-in-both-parties/

2. Politics, III.7. (Benjamin Jowett trans.) Aristotle is the initial fount of republican wisdom, even if we are unlikely to label him as “republican” overall.

3. Jim Norman, “Half of Americans Favor Mandatory National Service”, Gallup, 11/10/2017. Online at https://news.gallup.com/poll/221921/half-americans-favor-mandatory-national-service.aspx . Not surprisingly, the idea was much less popular among those who might actually be affected.

4. In Tools to be Free (Lexington Books, 2024), I propose significantly expanding voluntary national service programs as a way to create a universal pathway to post-secondary education. Mandatory programs, except in times of real emergency, do not pass liberal tests of legitimacy. I will eventually write about this in this space.

5. I want to distinguish here between oligarchs like Elon Musk, who are actively capturing the state, and most of the rest of the corporate aristocracy, who, it seems to me, are defensively complying with the autocrat to minimize the risk to their companies and personal fortunes. Shame on both, but keep-your-head-down cowardice is a different order of moral offense than the kleptocratic coup.

6. Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, Volume 2, Part II, Chapter 8.

7. https://abcnews.go.com/blogs/business/2012/01/warren-buffett-and-his-secretary-talk-taxes

8. In a 1953 Congressional hearing on his nomination for Secretary of Defense, Charles Wilson, President of GM, said “for years I thought what was good for our country was good for General Motors, and vice versa.” This is often misquoted to say only that “What’s good for GM is good for the nation.” That’s still probably a valid statement, but much more arrogant. The issue was whether Wilson should divest himself of GM stock to become secretary; he did. https://blogs.loc.gov/inside_adams/2016/04/when-a-quote-is-not-exactly-a-quote-general-motors/

9. Philip Pettit, On the People’s Terms (Cambridge, 2012), 84, 86.