Post 19: 6 May 2025

Access to post-secondary education ought to be guaranteed by governments as a social right of citizenship. I’ll use the shorthand “college” here, but I mean any program of education and training that normally is appropriate only after completing high school. The programs might range from “traditional” four-year college courses to much shorter training programs that may focus on skill acquisition, including in the trades.

Today, I will make the general case for why we should strive for universal college access. Next week, I’ll present a program of specific reforms.

The operational principle of social citizenship, which I often repeat, is that everyone ought to have a set of life choices that are comparable to others in society and the capability to choose among them. Is college one of those choices?

The word comparable does a lot of work in this imperative. What line does it draw? I do not mean that every opportunity ought to be available to every person. As we proceed, I can say more about the contours of opportunity under social citizenship, but briefly, it falls on us to define the set of choices that ought to be open to all as part of our shared membership in society. To a large extent these choices evolve organically—the things we all ought to be able to choose are those things that most of us recognize as valuable choices in our own lives—with legal and programmatic protections following behind. If this seems circular, it is because the standards of social citizenship are reflexive; they reflect current, evolving, social standards. People demand that they have full access to the rights and powers available to others and they demand to be included in a meaningful way in the shared material culture.

The first argument that post-secondary education ought to be in that set of life choices is that a majority of Americans do in fact pursue this life option after high school. In October 2024, 62.8% of the most recent high school graduating class were enrolled in colleges and universities.1 Sadly, at last measure, only 62% of those entering college complete their degree within six-years, so the percentage of Americans with a college degree seems stuck at about 38%.2

Those data refer to our traditional degree-seeking idea of college. My argument is not that everyone needs this sort of education—though my bias lies in that direction—but that college ought to be an option for everyone.

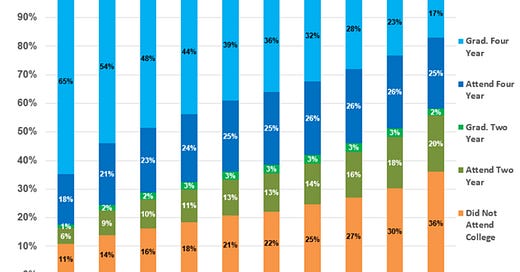

Presently, it is not. A few years ago, the College Board began building statistical profiles of American high schools and neighborhoods as a way to give admissions officers at selective colleges and universities some context about students’ resource environments. The chart below breaks out American neighborhoods (census tracts) into ten equal sets (deciles). In the ten percent of neighborhoods scored as best resourced (“least challenged” in their parlance, left side of the chart), 89% of high school graduates attended some sort of college and 66% graduated with some degree. In the least well-resourced decile (right side of the chart), a majority of 64% attended college—again reflecting how common an aspiration this is—but only 19% left with a degree.3

There’s a lot in this chart. [If you are having trouble seeing it, you can follow the link in the footnote to see the original.] It shows, for one thing, that a strong majority of high school grads, regardless of their socioeconomic background, seek out a college education. The stats also show that, formally, the post-secondary system is open. Students from the poorest neighborhoods and weakest high schools aspire to attend college, including very selective ones, and some reach this goal. But the only students regularly succeeding in these aspirations are drawn from the most well-resourced 20% or so of American society. The college completion problem mentioned above is evident across the board, but for the bottom 20% or so of students, a majority who attempt a four-year degree fail.

The second reason why everyone ought to have access to college is that the range of occupational choices open to college graduates is much greater than for others. About two-in-five occupations on a list kept by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) typically require at least college degree. If we count occupations that require significant training, but not necessarily a degree—pilots, firefighters, dental hygienists, and so on—then nearly half of all the jobs they list require post-secondary education.4

The set of “college” jobs also pay better, much better. In the most recent annual snapshot, workers with a BA (and no higher degree) earned 66% more than those with only a high-school degree. The college wage premium has shifted greatly over time as opportunities in manufacturing and the trades have waxed and waned—this is worth its own post—but it has been much too high in this century. Better minimum wage protections would raise the wages of the least well educated the most, so that is definitely part of the solution.5

A college degree, then, is a gateway to a broad set of occupational choices and a generally higher standard of living. It is, in short, a marker of social class. I would like that to be less true. Regardless, advanced education expands choices for people. Again, our first principle is that everyone ought to have comparable life choices. There is simply no way for that to be so if we do not all have a reasonable opprotunity to graduate from college.

The value of a college education holds, more or less,6 regardless of the socioeconomic background of the student. A college education can be, and often is, the key to upward social and economic mobility for students from less advantaged backgrounds.

This leads us to an awful paradox. Because poorer students are much less likely than their more advantaged peers to attend and then graduate from college, the system of higher education is more likely to help reproduce and strengthen the stratifications of social class than it is to erode those divisions by serving as an engine of opportunity in American life. Unless we solve the access problem to post-secondary education, we won’t be able to realize the gains in social mobility that college promises.7

Whether or not everyone ought to attend college, however we define that, I should not be able to predict whether a student attends, and then graduates, from college based only on their ZIP code or their parents’ educations or incomes.

My next post will focus on my own proposal to restructure access to post-secondary education in the United States. I seek to build a universal pathway that can provide all Americans with a common set of choices and opportunities as they transition from adolescence to adulthood, a set of choices not dependent on parental income or education. These ideas will mostly be drawn from my book, The Tools to be Free: Social Citizenship, Education, and Service in the 21st Century.8

The most obvious criticism of any proposed reform to the post-secondary educational system is that colleges are not, in the main, responsible for the college access problem. It’s mostly a “pipeline” issue, isn’t it?

It’s true that the most logical and effective way to “fix” the problem of college access would be to improve the system of primary and secondary education to the point at which every student could graduate from high school fully prepared for the full range of life choices that we as a society feel young adults ought to have. This is obviously true, and I will be examining aspects of the K-12 system in subsequent posts. Moreover, I keep arguing in this space that we must advance all of the social rights of citizenship in a coordinated way because the different spheres interact so often. This is the simplest instance for that principle.

I have mixed feelings about the K-12 system. Overall, the system works better than critics, including me, generally acknowledge. There are large gaps across the resource spectrum, as suggested in the complicated College Board chart I offered above, but kids from every type of community manage to graduate with a mostly workable education and in every type of community are served by dedicated teachers who, as far as I can tell, are always working to improve outcomes. On the other hand, the prospects of achieving significant improvements from this status quo are daunting. K-12 reform faces a set of very serious institutional barriers that go to the basic ways in which American life and government is organized. The root cause of our educational inequalities is the deep segregation of American society along economic and racial lines. There are things we can and must do, but it is an extremely heavy lift.

My proposals for post-secondary education reflect these prospects for K-12 success. There are things we can do right now to change our post-secondary system in positive ways that are not especially dependent on earlier educational outcomes. These will be politically easier to achieve than the deep reforms needed in primary and secondary education. Further, many of the changes I will propose will ameliorate the inequality generated by the K-12 system, at least at the margins.

More on this next week.

Next week: College Access as a Social Right II (13 May 2025)

All of the posts in On Social Citizenship connect. I recommend that readers go back and read the first entry in the series.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Median weekly earnings $946 for workers with high school diploma, $1,533 for bachelor's degree” October 25, 2024.

National Student Clearinghouse, “Completing College” November 30 2023 (2017 cohort).

Jessica S. Howell, Michael Hurwitz, Samuel Imlay, Greg Perfetto, “Educational Context Matters: The Development, Foundations, and Use of Consistent, Research-Based Environmental Information in College Admissions”, College Board Research, October 2022.

The chart reveals a major way in which the post-secondary system is tiered. The poorer kids aim lower, with 22% trying for community college, compared to only 7% of the wealthiest kids. Completion rates at two-year schools are much lower than at four-year ones. This is a serious problem that reflects how poorly we understand the needs of this population, but the statistic does not always reflect a “failure” and can’t be simply compared to the four-year version—many of these students were never seeking a degree. A more nuanced metric would adjust for students transferring to four-year schools and, this is harder, for those who leave when they are able to get the job they wanted.]

This list contains 832 occupations. I’m looking at this table: https://www.bls.gov/emp/tables/education-and-training-by-occupation.htm

The word require here can be problematic. The link between education and other opportunities is logical but some of the gaps are exaggerated. For example, there is some credential inflation built in BLS’s list of typical educational requirements. We could expand opportunity at the margins if employers, especially large employers, gave more weight to the industry and process knowledge that comes with experience and less to formal credentials when hiring.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, “College Enrollment and Work Activity of Recent High School and College Graduates Summary”, Tuesday, April 22, 2025.

This is a broad-brush statement, but it is true enough. Students from well-resourced backgrounds have advantages that continue to serve them well after college but success in college does a great deal to close the gap between students from poorer and wealthier backgrounds. That is, these students are a lot more similar at college graduation than they were at the end of high school. These patterns also depend on the type and general selectivity of the college they attend.

The Opportunity Insights program (Raj Chetty et al) highlighted the tension between access and mobility in a 2017 paper called “Mobility Report Cards.” The input data for this study is now dated (mostly the college Class of 2013), but the general pattern is clear. Highly selective schools, especially, do a great job of graduating their poorer students and launching them into life with great opportunities, but they educate relatively few of these students.

Stephen Minicucci, The Tools to Be Free: Social Citizenship, Education, and Service in the 21st Century, Lexington Books, 2004. Use promo code LXFANDF30 for 30% off (the very high list price).