Post 25: 17 June 2025

Today, I continue my exploration of Franklin Roosevelt’s Second Bill of Rights, with the last of the items on his list, but the first on mine:

And finally, the right to a good education

An adequate public education is the most fundamental social right of citizenship. It is also the most well-established social right we have in the United States. In a later post (soon) I will make the case that the “adequate” part of the right is not actually established in law—there is more work to do. Today, I just want to remind us why education is the foundation for everything else. That requires a little refresher about social citizenship.

Social Citizenship

The core principles of social citizenship derive from our conviction that every person ought to be treated as equal to every other in dignity and respect. They ought to enjoy that equality of status that is associated with full membership in the community. This abstract goal has substantive telltales. Full members of the community have a set of life choices that are comparable to everyone else and the ability to choose among them. They are able to participate fully in society, capable of using their civil and political rights effectively. These things require access to certain resources so our commitment to equal membership requires that we guarantee access to those resources—these are the social rights of citizenship. There is a lot of politics left out of this formula. It is not immediately clear which choices ought to be guaranteed, nor the set of resources these require. These details can only be worked out by closely examining each situation and talking it through. I try to do that in this publication, but ultimately, between the principle and the policy, democracy has to happen.1

The principle that unifies these considerations is freedom. Freedom requires that we both have the formal power to make private and public choices, powers embedded in our civil and political rights, and that we are in a position to make them. Social rights put us in that position; they give us the tools to be free.2 The scope of our civil rights are limited if we lack the resources to pursue justice in the courts, or if employers, lenders, and landlords have us at such an economic disadvantage we are nearly compelled to comply on their terms. Sometimes we have to go on strike. And sometimes we just have to be able to walk away from private relations of domination. Similarly, our political liberties are meaningless if we lack the time, knowledge, and resources needed to participate in the collective project of self-government. These limitations are the result of dependency, so one way to think about social rights is that they guarantee the minimum degree of personal independence each of us needs to be able to make the choices that are properly ours to make. This is the best way to think about freedom.3

The justification for any social rights claim must be found in the paragraphs above. The simplest rationales are for public protections against the full range of market outcomes, for setting rules or providing resources that prevent us from being priced out of our communities or our healthcare, for example, or that ensure that we have enough income to plan beyond this week’s groceries. These sorts of social rights focus on security, on creating a safe place to stand while navigating day-to-day life. They help us resist domination by minimizing the power of others to place us in a compulsory position; in that way, they promote freedom directly. But we must be concerned with more than the day-to-day. The central tenet of social citizenship, that we all ought to have a set of life choices that are comparable to everyone else and the ability to choose among them, is meaningful only over the course of a complete life. Only one social right operates at this time scale: the right to an adequate education.4

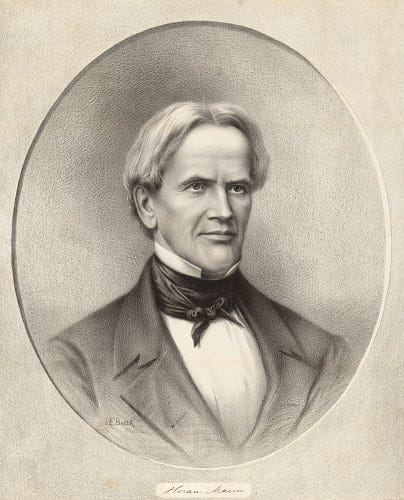

Horace Mann Explains It All

Many of the major choices we make in life concern or depend on education. That includes, obviously, our choice of occupation or profession, but education can also provide us with the tools we need when changing circumstances force us to adapt, and it also provides the basic human capital we need to engage with the full range of public and private questions we will face across a lifetime. Public education is an undeniable social right of citizenship. If it isn’t, it is hard to see what would be. Any chance of equal membership in society depends on an adequate primary and secondary education.

I could belabor this conclusion but instead I want to focus on specific point: This is about inequality. Social rights fight inequality by increasing the capacity of each person to confront and resist the specific forms of private domination they face in their everyday lives. The freedom we are talking about is very particular, even private; it concerns the personal capabilities of each individual. Every person has to have a certain level of personal and economic independence in order to truly have the status of a free person, a person who chooses. Importantly, this resists inequality from the bottom, by increasing the power of each person, not by penalizing the wealthy or through redistribution for its own sake.5

To drive this theme home, I call on Horace Mann.6 In his last report as secretary of the Massachusetts State Board of Education in 1848, he made clear the threat of inequality:

vast and overwhelming private fortunes are among the greatest dangers to which the happiness of the people in a republic can be subjected

He was speaking of the same kind of domination to which I refer. Comparing capitalism in his rapidly industrializing state to feudalism, he added, “What force did then, money does now.”

For Mann, the only meaningful response to the power of capital was education:

Nothing but Universal Education can counter-work this tendency to the domination of capital and the servility of labor

Without an adequate education, laborers become the “servile dependents”, the mere “subjects” of the owning class. But education is “the great equalizer of the conditions of men”:

it gives each man the independence and the means by which he can resist the selfishness of other men.

I could not have said it better.

Mann says a great deal more in these pages about the role of education in a republic. I will return to that theme soon, but here I wanted to emphasize the importance of education to individuals in their own struggles against the private centers of power in their lives.

The next post will continue exploring the basic theme of education as a social right.

Next week: TBD (an education topic) (24 June 2025)

<All of the posts in On Social Citizenship connect. I recommend that readers go back and read the first entry in the series.>

Notes

For full descriptions of the principles of social citizenship, see the first two posts in this series: Membership, Equality & Freedom, and The Idea of Social Citizenship. From time to time, I will find it useful to restate the first principles upon which this enterprise is based. I do this mainly to keep my own analyses grounded, but I hope it is helpful readers as well.

See my book: Stephen Minicucci, The Tools to Be Free: Social Citizenship, Education, and Service in the 21st Century, Lexington Books, 2024.

Several posts in On Social Citizenship deal with freedom: Real Freedom, Freedom and Social Citizenship, LBJ’s Forgotten Message on Freedom, and When We Redefined Freedom. Again, he exact level of resources implied is a matter for democratic resolution. None of us is ever fully “independent” but there is a minimum level of personal autonomy consistent with equality of status, full membership, and personal freedom.

In my entry on “Income as a Social Right” I started creating a taxonomy of social rights. Today’s musings add an important dimension to that analysis—the distinction between protections intended to maintain a status of adequate economic independence operating mostly day-to-day and policies intended to create or expand that status, operating over longer time frames. Education, mostly, is what operates at this level, but we might also include policies that support other “life decisions” here, including support for new enterprises and for family formation.

But the increased independence of ordinary people ought to have macropolitical implications, so it will also facilitate resisting the ills of inequality that are only apparent at that level; that is, the distorting effects of wealth on republican self-governance. Developing a robust scheme of social rights requires that the main focus of politics be debating the contours of the welfare state—deciding which life choices ought to be universally accessible and then determining the sorts of resource guarantees that follow from that. These are not the concerns of oligarchs, who will, presumably, always try to block progress. Social rights advocacy will therefore inevitably require limiting the disproportionate power of economic elites. But that is another essay altogether.

I will be quoting from the Twelfth Annual Report of the Massachusetts State Board of Education (1848), reprinted in part in Lawrence Cremin, ed., The Republic and the School (Teachers College Press, 1957), 79ff. Mann was the first secretary of the Massachusetts State Board of Education, later a member of Congress, noted abolitionist, and finally President of Antioch College. He is often considered the father of American public education. In his last address to the graduating class of Antioch College, Mann told his charges to “Be ashamed to die until you have won some victory for humanity.” That more or less sums up the man.